17th Century

A short history of the

Baronetage

The order of the Baronetage was

founded in May 1611 by King James I of

There are various classes of baronets

- those of

When first created, the order was limited to 200,but this limit has long been ignored.

For the first 216 years of the

existence of this dignity,

the eldest son of a baronet was entitled, on reaching adulthood,

to the privilege of claiming the honour of

knighthood. A clause to this effect was inserted in every patent of creation

until

With one exception only, all baronetage creations have been men. The sole exception was a baronetcy conferred upon Mary Bolles of Osberton, Notts in 1635. However, on a small number of occasions the baronetcy has been inherited by a female and can also descend through a female.

The descent of a baronetcy is governed by the same rules as in the case of peerages i.e. to heirs male of the body (unless there is a special remainder outlined in the patent, or, in the case of most patents granted by Charles I,where the patents were to heirs male whatsoever).

Baronets of

Precedence amongst baronetcies is decided by the date of creation alone.

The Official Roll of the

Baronetage is administered by the Standing Council of the Baronetage, first

formed in 1898 and re-constituted in 1903. Two of the objects of that Council

are to publish an Official Roll and to advise heirs apparent to baronetcies on

how to prove their claim and, as a result, to be entered onto the Official

Roll. As part of a Royal Warrant of Edward VII dated

Copyright © 2003 Leigh Rayment

|

BARONETAGE: TUITE of Sonnagh, Westmeath |

|||||

|

Succeeded to the title |

|

Name |

Born |

Died |

Age |

|

|

1st |

Oliver Tuite |

c 1588 |

1642 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1642 |

2nd |

Oliver Tuite |

c 1633 |

Aug 1661 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Aug 1661 |

3rd |

James Tuite |

|

Feb 1664 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Feb 1664 |

4th |

Henry Tuite |

|

May 1679 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

May 1679 |

5th |

Joseph Tuite |

1677 |

1727 |

50 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1727 |

6th |

Henry Tuite |

c 1708 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

7th |

George Tuite |

|

|

52 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

8th |

Henry Tuite |

1743 |

Aug 1805 |

62 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Aug 1805 |

9th |

George Tuite |

|

|

63 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

10th |

Mark Anthony Henry Tuite |

|

Mar 1898 |

79 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Mar 1898 |

11th |

Morgan Harry Paulet Tuite |

|

|

85 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

12th |

Brian Hugh Morgan Tuite |

1 May 1897 |

|

73 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

13th |

Dennis George Harmsworth Tuite |

|

|

77 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

14th |

Christopher Hugh Tuite |

|

|

|

Sir Oliver Tuite, the 1st

Baronet of Sonagh died in 1642. He was succeeded by

his eldest grandson, (oldest son of Thomas who died in 1624) also named Oliver.

Mary Tuite (daughter of Sir Oliver

Tuite, 1st Baronet of Sonagh) married Colonel Patrick

Plunkett of Louth.

Thomas Candler, esq. (c1663-1716 or

c1641-1715), inherited the title and Callan Castle

estate of his father William (who had come to Ireland during Cromwell's Irish

campaign and won, "by meritorious conduct in the field", a promotion to Lt.

Colonel and was granted the Barony of Callan by a

grateful Cromwell and Parliament in 1653). In 1685/86, Thomas married, first,

Elizabeth Burrell, daughter of Capt. William Burrell and Elizabeth Phipps.

Capt. Burrell had served with

William Candler under Sir Hardress Waller during

the Irish Rebellion

and had received land in Burnechurch in County Kilkenny, not far from Callan. Elizabeth Burrell Candler died before 1694 without leaving

any surviving children. In 1697, Thomas Candler married again, to Jane Tuite

(b.1677/79), daughter of Sir Henry Tuite, Baronet of Sonnagh, County Westmeath

and Diana Mabot (or Mabbot)

who was a niece of the late Edward Hyde, Earl of Clarendon.

Sir Henry Tuite was a direct

descendant of Sir Richard de Tuite, knight, who had

accompanied Strongbow

to Ireland in 1172. Though the Tuites were

Norman-Irish Catholics and technically classified as Anglo-Irish, after more than

400 years on the Emerald Isle they were

Irish to the

core. Their family lands in

Westmeath and Longford were confiscated by

Cromwell in 1654 and the

Tuite family was

banished to Connaught Province. They regained most of

their lands after the Restoration (1660) only to be threatened with loss

again after the defeat of the Irish Jacobites by

William of Orange in 1789.

The circumstances

surrounding the marriage of Jane

Tuite, a baronet's eldest daughter and a Roman Catholic, to Thomas Candler, who

was a Protestant and whose family's social rank was that of an esquire, two

notches on the gentry ladder below Baronet is interesting.

Given the times, it is possible that Jane Tuites

marriage to Thomas Candler may have been an alliance of considerable value and

political security to the Tuite family. However, there are other possible

angles to the Candler/Tuite marriage.

Diana Mabot

Tuite, Jane's mother, was also a first cousin of the Duchess of York who was

mother of Queen Mary (William & Mary) and future Queen Anne. Diana's

parents were Kympton Mabot and Susan Hyde,

Edward Hyde's sister. (Edward Hyde's daughter, Anne, was one of the wives

of James II. Anne's oldest daughter, Mary, was on the English throne when

Thomas Candler married Jane Tuite).

Thomas and Jane Tuite Candler had four

sons: Henry, William, Thomas and Daniel. (The Burke and other references on the

Peerage, etc. do not include Daniel among the list of children reportedly the

result of his "disownment" by his family for marrying an Irish woman

(who may have been a servant in the Candler household). Daniel's assignment to Thomas rather than brother John is based

on the fact that

John reportedly died several years before Daniel was reportedly born.)

Of their four sons, Henry and Daniel made the biggest mark. Rev. William Candler (c1699-1753),

Thomas and Jane's second

son, earned a doctor of divinity

degree and served the church of Ireland initially in Dublin and later as

rector of St. Mary's Church in Castlecomer, County Kilkenny. The fourth and youngest son, Daniel Candler was

born at Callan Castle in County Kilkenny, probably

about 1706.

Eleanora Tuite, daughter of Sir Edward Tuite, died, April 8th

1638. She was married to Theobald, 1st

Viscount Dillon (who died 15 March 1624).

Father James Tuite was deported to the Caribbean on the slave

ships with other Irish by Cromwell’s English forces in 1650/51 for his part in

the Irish rebellion. Richard and Thomas Tuite both defended Bective

Abbey in Meath in a 1650/51 against Cromwellian

forces.

The Tuites fought with the confederates

in 1641 and on the side of James Stuart in 1690.

There is a famous early seventeenth century political song , titled “As I rode down by Granard

Motte”, mentioning the Tuites

in a book by the well-known Irish poet Benedict Kelly.

|

The Edgeworth Family –

Early History |

|

The first Edgeworths

to come to Ireland in 1585 were Edward and Francis, natives of Edgeworth or Edgware a town in Middlesex near London. Edward the elder became bishop

of Down and Connor while his brother Francis entered the law in Dublin and

was appointed to the office of Clerk of the Crown and Hanaper. In

1619 he was granted some 600 acres of land near Mostrim

by King James I. His third wife was Jane Tuite daughter of Sir John Tuite of

Sonnagh in Westmeath. Their son John was brought up in England and returned

with his wife to live at the castle of Crannelagh

(Cranley). He was absent when the rebellion broke out in 1641, when his wife

and three year old son also John were saved from death and smuggled to

Dublin, by a ruse by Edmond MacBrian Ferrall a servant of the household. He also saved the

castle from destruction by fire. This son settled later in Lissard. He was somewhat of a gambler and spendthrift but

in 1670 bought the lands of Mostrim now Edgeworthstown, though it was many years later that it

became the home of the head of the family, when his son Francis came to live

there at the end of the century of the death of his father Sir John, who

although knighted in 1671 by the Duke of York later took the Williamite side at the revolution. In the meantime he had

left Lissard to live at Kilshrewley,

but much of his life was spent in the Army and in England. One of his sons

Henry later came back to live in the old house at Lissard. Sir Johns grandson Richard was

left a penniless orphan at the age of' eight and was brought up by his half

sister in Packenham Hall in Westmeath. At the age

of 18 in 1719 on the death of his half sisters husband, Edward Packenham, he had take over the estate and paid off the

debts of his father and grandfather and recovered losses incurred by the

malpractices of his uncles Robert and Ambrose. He it was who built the house

in the 1720's we know today. It was built around an earlier house presumably

that occupied, about 1697 by his father Francis. He was the author of the

Black Book of Edgeworthstown an estate record that

tells us so much about the locality at that time. By

John Mc Gerr Another

description is as follows: MARIA EDGEWORTH BY THE HON. EMILY LAWLESS

Francis Edgeworth

married the daughter of a Sir Edmond Tuite, owner of a place called Sonna, in the |

Jane Tuite

Making

Ireland British: 1580-1650 by Nicholas Canny

The

Irish Insurrection of 1641

Except

pages 517-518

Religion was never treated as a discrete matter and allegations relating to the

humiliation of the queen and the proposed assault upon Catholicism quickly gave

way to reports of challenges to the royal prerogative by the English parliament

which mingled what had happened with what might ensue. It was alleged by some

Catholics that the parliament had used the king so ‘harshly’ that he had

‘departed into Scotland and from thence he would come into Ireland and destroy

all the English there’. It was only a short step from there to suggest that the

king had been dethroned by the parliament ‘and would not return into England

for the English had a king, the Palsgrave, and had

banished the queen to France’. Others had contended that the queen had found

refuge in Ireland and ‘that this kingdom of Ireland would the queen’s

jointure’, and that she would take up residence there ‘and clear England of all

Papists’. Some went further to claim that the king also was on their side and

‘that the English were proclaimed traitors, and that the king was in Scotland

and would be in Ireland within nine days and would banish all the English’.

Most dramatic was the assertion of one Welsh, an innkeeper of Kilcullen, County Kildare, ‘that the king was in the north

of Ireland and ridd disguised and had glasen eyes because he would not be known and that the king

was as much against the Protestants as he himself and the rebels were, for that

the Puritans in the parliament of England threw libels in disparagement of the

king’s majesty making a question of whether a king or no king’.

All of these rumours, allegations, half-truths, and suggestions

show that those in Leinster who became involved in and insurrection, which they

sincerely believed was designed to frustrate and anticipated blow against

Catholicism in Ireland, experienced little difficulty in convincing themselves

that their actions were also intended to support the king and queen. This lent

credibility to the frequently made claim that the insurrection had been

previously approved by the king, and all these rumours and claims were widely

believed by Catholics because they contained sufficient elements of truth to

make them plausible. What the relative roles of priests and laity were in

devising these justifications for revolt, and in guiding the insurrection, is

unclear, but everything suggests that the Catholic clergy in Leinster exerted

more influence over the course of events than in the other provinces. Indeed

some believed the priests were so influential there that they had, as in

Connacht, undermined the authority of the Catholic landowners by stirring up

the populace over religious issues. Those Protestant deponents who made this assertion

alluded to meetings convened by the Catholic clergy previous to the insurrection, especially that supposedly held at Multyfarnham, County Westmeath, on 3 and 4 October 1641.

The clear implication was that plans were there laid for the revolt without any

reference to the Catholic laity, and Randall Adams, a minister at Rathcouragh, in the same county, reported on a conversation

he had overheard on 1 November 1641 between some of the ‘chief gentlemen’ of

the county and a group of friars. The gentlemen, mostly members of the Tuite

family, laid a charge against the friars ‘that they and their fellows were the

cause of this great and mischievous rebellion’. They further asserted that the

friars had had no cause of grievance that would justify such extreme measures

because of ‘the great freedom they had in religion without control, and that

they generally had the best horses, clothes, meats, drinks and all other sort

of provision delightful of useful … and they had these and many other

privileges beyond any of their own function either regular or secular through

the Christian world, and therefore most bitterly them to their teeth said that

they hoped God would bring that vengeance home to them that they by their

cursed plots laboured so wickedly to bring upon others’.

This discourse, if it can be taken at face value, alludes to a

tension that had been developing between the Catholic gentry and continentally

trained priests in Ireland ever since the 1620s, and that was to become even

more acute after 1642 when the clergy began to play an active role in Irish

politics. Previous to then, as far as the Catholic landed interest was

concerned, it was they, through their parliamentary representatives and

delegations to court, who had negotiated toleration

for Catholicism, and they obviously wanted religious freedom to be on the terms

they sought after. This involved Catholicism and the Catholic clergy

functioning under the protection of their patrons but within a state system

that was officially Protestant. The Catholic clergy, for their part, were

becoming impatient with this argument, first because it facilitated Catholic

lay interference in church affairs, and second because it denied them the

right, or indeed the opportunity, to practise Catholicism openly as was the

norm in the continental societies of which they had experience. It would seem

therefore that the clergy, led by some of their seminary-trained bishops,

welcomed the opportunity to make a bid for the full public recognition of

Catholicism which would have involved a recovery of cathedrals and churches

that had been lost to the state religion, as well as the lands, tithes, and

other duties that had traditionally belonged to the Catholic Church. It has

long been accepted, and has recently been detailed by Tadhg

O hAnnrachain who has worked for Catholic

ecclesiastical sources, that these ambitions were in the minds of some senior

Catholic clergy before 1641 and were expressed openly by them from the moment

the Confederacy was established, and most especially from the time that it

received official recognition from the papacy. Therefore it is not at all

unlikely that the Catholic clergy, who were more firmly established in Leinster

than in any other province in Ireland, took advantage of the collapse of government

authority in most parts of Leinster, beyond Dublin and a few fortified

outposts, to articulate deeply held ambitions which their lay patrons had

always refused to countenance and which they now believed would provide a moral

underpinning to the insurrection that was already underway. Thus what Donatus

Connor had to report from County Wexford seems entirely credible: he had, he

said, ‘frequently heard the rebels say they would never give up (even if

pardoned) unless that all the church land of Ireland were restored to the

churchmen of the Romish religion and that they might

enjoy that religion freely and the Protestant religion might be quite rooted

out of this kingdom and that the church of Rome might be restored to its

ancient jurisdiction, power and privilege within he said kingdom of Ireland’.

Those landowners, like the Tuites of

County Westmeath, who were secure in their property would have had no time for

such an agenda, first because they were themselves likely to have been owners

of former church lands which they would have acquired after the dissolution of

the monasteries, but also because they would have recognized that the agenda

could only have been achieved through revolutionary action which would have

placed their lands and positions in jeopardy. This would explain why the

Catholic clergy in Leinster had to speak over the heads of such conservative

landowners, and in doing so unleashed a peasant fury which they were able to

control only somewhat more effectively than their counterparts in Ulster and

Connacht.

The inability of the Catholic clergy to keep the uprising on a

strictly religious course even in the areas dominated by the Old English is

explained by a variety of factors. First, as in the case of County Wicklow,

some landowners were acutely dissatisfied with the government, and those who

fostered a sense of grievance over what they had lost in the various

plantations believed they had an opportunity to recover their losses, at one feel swoop. Besides the Byrnes, O’Tools,

and Kavanaghs of Wicklow, there were some landowners

in Counties Wexford and Longford as well as King’s and Queens’s counties who

were ready to take advantage of the breakdown in authority to meet these purely

material ends. These were willing to echo the religious message of the clergy

or to express concerns over the plight of the queen and royal prerogative but

their ultimate concern was that their lands had been assigned to English and

Scots who now ‘liveth bravely and richly’ while ‘they

and the rest of the Irish were poor gents’. Their objective therefore was to

cancel all the plantations that had been established in Ireland after the

principle, articulated, also in the other provinces, that as ‘the English held

their own lands in England, and so did the Scots in Scotland and so should the

Irish in Ireland’. The fulfilment of this principal require that since ‘both

the English and Scottish which were in Ireland were all beggars when they came

into Ireland so should they be turned thence’. But besides clearing the settlers

from their former possessions these landowners were, as we saw, interested also

in spreading the insurrection outwards from their own counties. They were

concerned to do so because they recognized that their gamble could succeed only

if they could gain political control everywhere in Ireland, and create a

situation whereby ‘they would never have any more chief governors, judges,

justices, or officers of the English or Scots but would name and appoint such

themselves’.

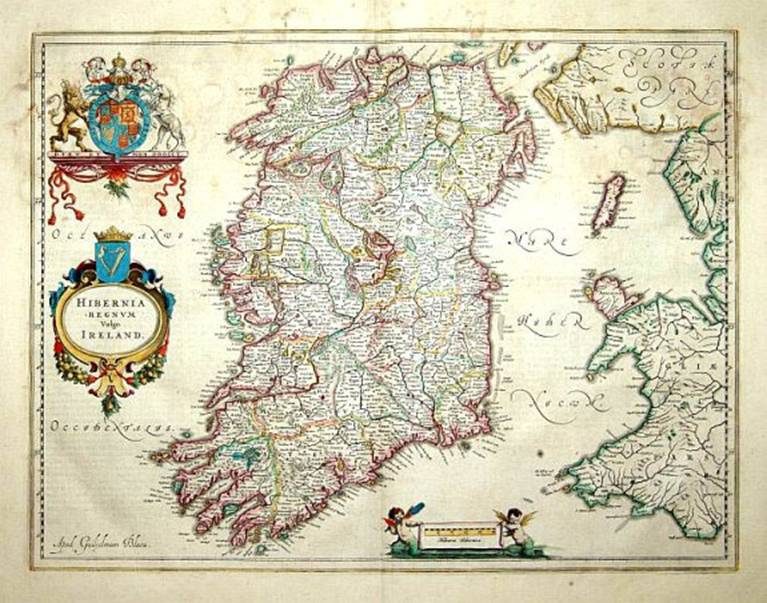

Map of Ireland 1650